Why don't libertarians like privacy anymore?

Digital privacy should be THE defining issue for liberty's loudest defenders, but they're asleep at the wheel.

I was putting the finishing touches on this essay when Michael Shellenberger’s post about Larry Ellison’s dystopian project came across my feed:

As founder of Public and professor at University of Austin, Shellenberger has plenty of credibly independent, anti-authoritarian, free speech-loving bona fides. It was nice to see at least one libertarian-leaning thought leader articulate the case against the censorship-industrial complex.

But other than him, it feels like the rest of the libertarian establishment is sleeping on the job, if not actively complicit. Let me tell you a story.

It was through a happy query accident in the dim antiquity of my university years that I found Institute for Human Studies and discovered my libertarian DNA. I had turned to Google’s then-pubescent search engine to register my distaste for both the anti-intellectualism of the Bush years (oh, how his “Is our children learning” and other “Bushisms” seem adorable by today’s incoherent standards) and the self-defeating delulus of the increasingly disaffected left.

Is there anyone out there, I asked Google, who shares my rejection of this whole impoverished dichotomy?1

And that is how I happily fell in with a merry band of discontents we call the small-L libertarians: socially liberal, economically conservative, rhetorically superior to the big-L party hopefuls and much more palatable at a real party.

It was the halcyon years — the early aughts — when Chris Hitchens held court at the bar to debate anyone over beers, and the national conversation was shaped by a remarkably civil dialogue between The New Republic and The Weekly Standard (where I would eventually work).

Still in college, my work-study ass was periodically whisked off on all-expenses-paid nerd junkets facilitated by IHS to an improbable oasis of lofty ideas, mildly famous people, and the promise of a dignified human future built on durable foundations of individual liberty, free and open discourse, and Enlightenment ideals. And all I had to do in exchange was make it through IHS’ hefty pre-reading packets without skimping on my finals — a fair trade because those readings opened portals to a pantheon of economist-philosopher heavyweights whose work taught me how to argue eloquently and show receipts. It was perfect.

We disagreed with the left because the reactionary nature of Crisis and Leviathan policymaking bloated the U.S. Code with public choice externalities that required even more whack-a-mole legislation to address each new set of have-nots it produced —but we vibed with their benevolence and EQ!

We disagreed with the right because of the prurience of their Biblically accurate pearl-clutching, but we vibed with their internally-consistent prescriptions for fiscal responsibility and minimal statism. This generated a rarefied Venn diagram of people who were smart, but also cool, but also few enough to fit into the Dupont offices for Reason Magazine’s happy hours.

No, really, it was perfect.

The policy struggles of that era made the period pieces in David Boaz’ The Libertarian Reader come alive. For example, I saw the Supreme Court twist the Takings Clause to deprive Susette Kelo of her private domicile because it sat inconveniently on some prime real estate that the city decided served some arbitrary state-determined public benefit. That was an L.

But we also caught a W when colleagues and friends at the Cato Institute and Tech Liberation Front mounted a principled defense of Section 230, the shield that kept early platforms from being sued into silence in the name of speech moderation while entrenching tech incumbents.

This is the fertile soil in which I, a budding privacy advocate, fairly blossomed. More importantly, it gave language to what I knew in my bones: never trust and always verify power because, trust me, I’m from Russia.

After I left DC, I ventured outside the professional libertarian sphere but stayed in orbit, never straying far from my principled, austere stance on government — and any accumulation of power for that matter, be it state or enterprise, that began to encroach on people’s ability to think their own thoughts and live their own lives.

Their ideas followed me like spirit guides throughout my career beyond DC’s gravity well — in corporate media in New York, in humanitarian work abroad, and later in the cozy web corners of crypto and cautious techno-optimism. The discourse in these tech circles often fixated on erosion of individual privacy, market distortions by incumbents, and the chilling effects of surveillance, the very favorite topics of the libertarian chattering class, or so I thought.

And I, faithful to my roots, held my ground against calls for ever-mounting regulation with the gospel of economic dynamism, minimum viable policymaking, respect for user autonomy, and a default-skeptical stance towards any centralization of money and influence for all the usual libertarian reasons.

So when Meta (then Facebook) got into hot water in 2016 for allowing a political campaign to scrape millions of users’ private data without their consent, I assumed libertarians would be the first to call foul. The classical-liberal-to-digital-privacy pipeline seemed so clear!

Here’s John Stuart Mill, for example:

“Genuine freedom of thought and discussion requires not only liberty of expressing opinions, but liberty of forming them; of pursuing the mode of life which to one’s own judgment seems best.”

…which easily becomes Julie Cohen's “spaces for free moral and cultural play” that she writes are necessary to preserve for “moral autonomy” and “independent critical thought”.

Or take Friedrich Hayek:

“Freedom means that the individual is in a position to choose and to carry out his own plan… It requires that the individual be protected from coercion, from the arbitrary will of others.”

…which sounds a lot like Daniel Solove writing that privacy isn’t about having something to hide, but because “surveillance can lead to a chilling effect on people’s behavior, altering the way they act in significant and often harmful ways.”

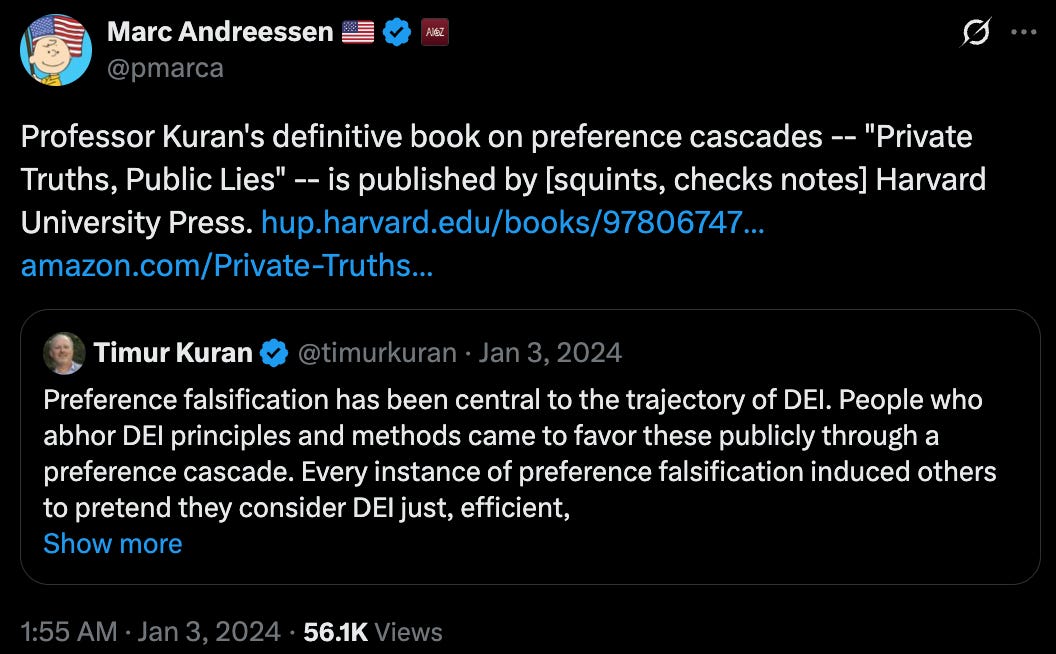

The case for digital privacy as a libertarian policy priority seemed fairly open-and-shut when Marc Andreessen, the patron saint of then-let-them-eat-innovation, got on the socials and podcast circuit to make the case against preference falsification for me. In surveilled spaces, people censor themselves, hiding what they truly think for fear of getting canceled or losing their job and their relationships. That makes it nearly impossible to measure real sentiment, leaving societies blindsided by sudden political upheavals, shock election results, and wild swings in public opinion — shifts that confound pollsters because the discontent never showed up in their data. This is why communist regimes so often failed to anticipate their own downfalls: everyone concealed their true beliefs until one loose seam unraveled into open revolt.

As I put it in my thesis:

People need privacy not to conceal illicit activity, but to avert social disciplining effects, without which their choices fall subject to decisional interference (Solove 2007). Because they generally fear the disapproval of their peers, individuals in surveilled spaces self-censor, falsify their preferences, and communicate ideas that differ from their true perspectives, generating a distorted view of reality. The accumulated misrepresentations of people’s real thoughts and sentiments achieves increasingly genuine social acceptance and normalization over time, leading to what philosopher Jeffrey Reiman calls psychopolitical metamorphosis (Nissenbaum, 2010).

By placing our survival needs for social approbation above our developmental needs for individual agency, surveilled spaces invite confirmation bias and groupthink. Individuals become more susceptible to social pressure and propaganda, especially if shared by those they wish to emulate or impress. Thus, even if people have nothing whatsoever to hide, surveillance materially alters perceived social norms and expressed behaviors.

Andreessen even quotes Timur Kuran, a guy whose work informed large parts of my research, leading me to coin the term “agentic tech” and start building this tech category in the first place!

It is hard to imagine Smith or Locke writing favorably about systems that make large-scale censorship and behavior modification possible. After all, much of the libertarian dialectic is built on the bedrock idea that we have certain inalienable rights, and that among these are most assuredly life and property. Our bodies conveniently meet both criteria: they house our lives, and, as of 1865 at least, these lives are the sole property of the person living them.

In the modern age, data is our digital body. Data is our avatar in the digital domain, and it betrays our internal workings and innermost thoughts in ways our fleshy avatar cannot: unless you’re trained to read micro-expressions, body language, or biometric cues, most of what truly makes up a person — preferences, foibles, desires, and fears — remains hidden.

But the digital body is an avatar with no skin. It renders us transparent by default: a few keystrokes, a well-trained algorithm, and suddenly the contours of our psyche, the seams of our behavior, the very architecture of our decision-making are laid bare.

This inversion matters. In the physical realm, the presumption is privacy: I do not know your thoughts until you choose to speak them. In the digital realm, the presumption is exposure: I must fight not to reveal them. That is why the analogy to the body is not a metaphorical flourish but a conceptual imperative. If life and property are inalienable rights, then the digital body — comprised of data that both represent and convey us from place as atoms do in physical space — demands the same respect for consent, integrity, and self-determination.

“Every man has a property in his own person,” writes Locke in his Second Treatise of Government. We may debate what parts of the digital body belong firmly to the individual and which fall into the public domain (see: interaction data). But those definitional vagaries do not negate the larger principle: sovereignty over one’s digital body should be of acute interest to anyone serious about preserving liberty in the physical realm.

Indeed, the very fact that the boundary between personal and interaction data is unsettled should invite vigorous debate from those who typically scream loudest about personal liberty. If property rights mean anything, then we need some property rights-minded people to chime in on where so much of modern life now unfolds.

So imagine my befuddlement at discovering, at a few seminars for notable free market thinkers that I recently attended, that libertarians are largely illiterate on the issues surrounding data privacy. Worse, many dismiss it outright as a “leftist” concern. One person, with a straight face, told me: “Surveillance capitalism isn’t a serious issue because Shoshana Zuboff is a communist.”

Zuboff, whose The Age of Surveillance Capitalism brought the term into the zeitgeist, is not a communist. And even if she were, that would be irrelevant. To dismiss her entire analysis on the basis of her perceived political leanings is to commit a basic category error — conflating the merits of a diagnosis with the author’s ideological orientation, or judging an argument by its source rather than its substance. Zuboff’s calls for stronger regulation of Big Tech are policy prescriptions, but they don’t erase the accuracy of her underlying diagnosis: that extractive data practices generate pervasive surveillance. Thoughtful analysts should have no trouble separating an account of the problem from a proposed solution to it. I found this argument, coming from a professor of economics no less, especially juvenile.

But this vacuous comment provided me insight into the potential source of the problem: I suspect libertarians are illiterate on data privacy simply because they’ve ceded intellectual ground on this to their perceived opponents. Organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center have been among the few engaging the topic with rigor. As a result, privacy discourse became coded as “leftist” by default — not because markets are incompatible with digital privacy, but because libertarians walked off the field.

I tried again more recently to raise the case for digital privacy among a similar group of libertarian luminaries. I thought it would be different this time, as the crowd was younger and more versed in tech than the previous cohort, whose focus was regulatory policy. But again, the same reaction, which betrayed not an informed rejection of digital privacy on market-based grounds, but rather a lack of engagement with it altogether.

Absent a nuanced grasp on how data, surveillance, and free societies fit together, they defaulted to familiar tropes: innovation solves everything; it’s fine as long as the government isn’t doing it; platforms engage users in a fair market exchange. I tried pointing out the fallacies, but without thoroughly updating their priors, I probably came off as a closet socialist and tech de-celerationist secretly bent on stymying the inexorable tide of innovation.

A sampling of what I heard:

“There’s no right to privacy.” (In fact, it’s implied in the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments, affirmed in landmark Supreme Court cases, and codified in statutory law.)

“Tort law solves this.” (Um, it doesn’t.)

“It’s a free market. As long as the government isn’t doing the spying, I’m fine with it.” (Ok boomer! Please uncringe yourself by watching this talk by Moxie Marlinspike, founder of Signal.)

These aren’t arguments — they’re reflexes. And they reveal not a principled rejection of privacy as a libertarian concern, but a failure to recognize digital property rights for what they are: rights, deserving of rigorous defense and the full-throated attention of anyone who claims the mantle of classical liberalism.

And this takes me back to the opening of this article: Larry Ellison, the richest man in the world, head of Oracle’s data empire, and soon-to-be owner of TikTok, Paramount, CBS, and, effectively, our attention spans — is openly touting a future where psychographic, biometric, and digital data are centralized so that no one misbehaves. He will also be steering the hyperscaler component of Stargate, the $500 billion public-private partnership linking Oracle, OpenAI, SoftBank, and the U.S. government. At this point, it should be obvious that the distinction between “company” and “government,” or “public” and “private” sector, is an antiquated heuristic.

If digital privacy still doesn’t register as a classical liberal concern — especially in the age of AI — then maybe Alex Komoroske, one of the founders in the agentic tech ecosystem, can spell it out clearer:

When your AI assistant is funded by keeping you engaged rather than helping you flourish, whose interests does it really serve?

The trajectory is predictable: first come the memories and personalization, then the subtle steering toward sponsored content, then the imperceptible nudges toward behaviors that benefit the platform. We’ve seen this movie before with social media—many of the same executives now leading AI companies worked at social media companies that perfected the engagement-maximizing playbook that left society anxious, polarized, and addicted. Why would we expect a different outcome when applying the same playbook to even more powerful technology? This isn’t a question of intent—the people at OpenAI genuinely want to build beneficial AI. But structural incentives have their own gravity.

To be clear, the centralization of AI models themselves may be inevitable—the capital requirements and economies of scale may make that a practical necessity. The danger lies in bundling those models with centralized storage of our personal contexts and memories, creating vertical integration that locks users into a single provider’s ecosystem.

The project of digital privacy should be a litmus test for anyone claiming the classical liberal canon. This is not about a leftist suspicion of markets or a Luddite rejection of progress. It is the recognition that markets only function when property rights are clearly defined and rigorously enforced. And how clearly defined are these property rights, I wonder, if their staunchest defenders are asleep at the wheel?

Back in college, a happy query accident on Google led me to libertarianism. Today, it’s libertarians who need to Google some very basic facts that, through their neglect, only those on the political and economic left have been writing about with credibility.

Asking whether digital privacy is libertarian issue is perhaps the wrong question.

The right question is: how is not our defining issue?

Not my actual search term, but similar in spirit.

AGREE